Once upon a time, there was a story about a girl in a red cape. Little Red Riding Hood has endured throughout the centuries, and her encounter with the big, bad Wolf of the nearby forest continues to be told to subsequent generations. Since Charles Perrault’s first publication of the narrative in 1697, “Little Red Riding Hood” has become a classic of children’s literature. Despite the various interpretations, one characteristic remains relatively intact with each version: the importance of clothing.

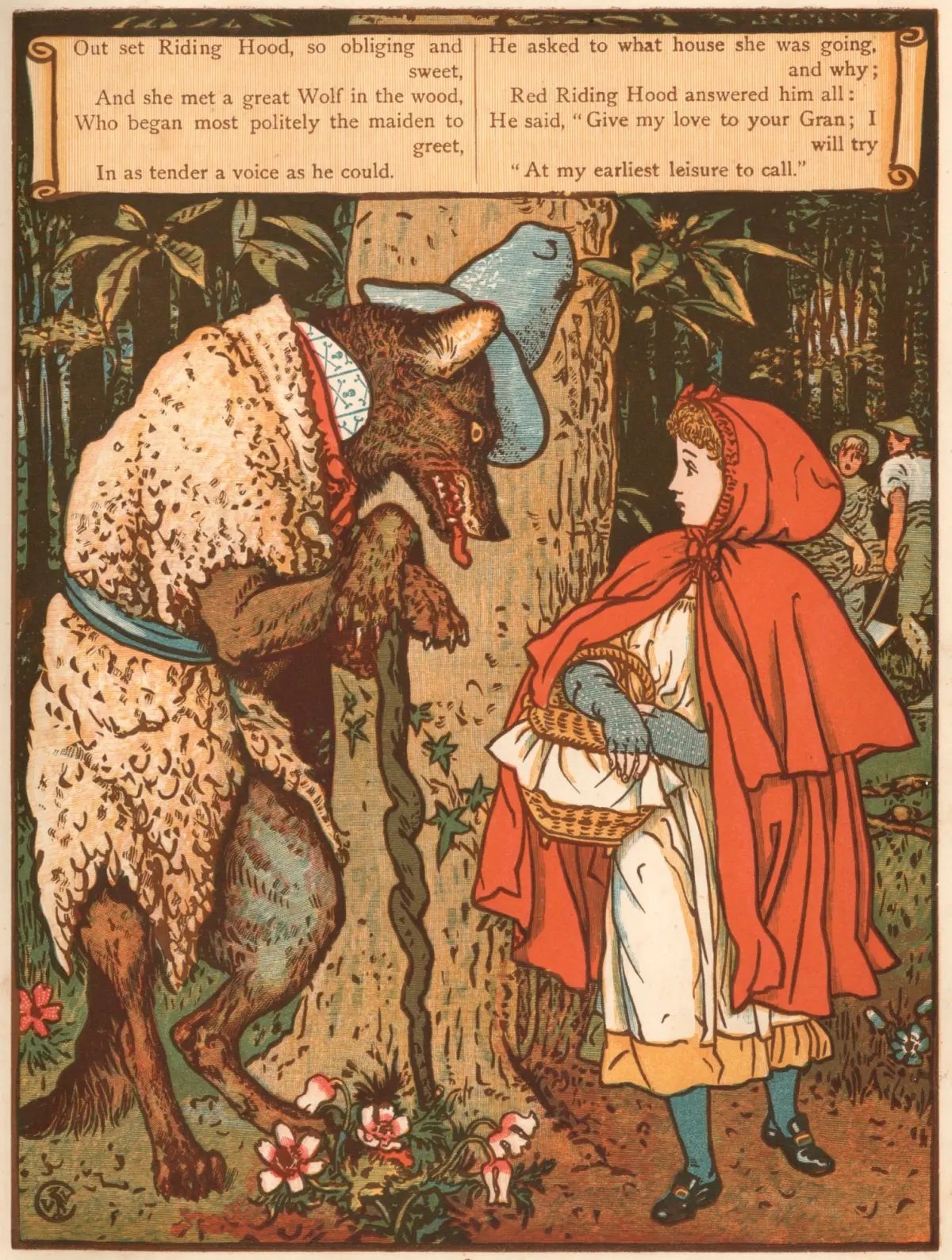

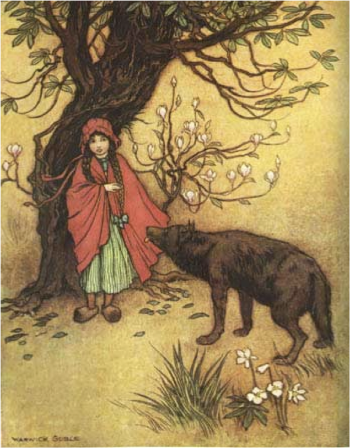

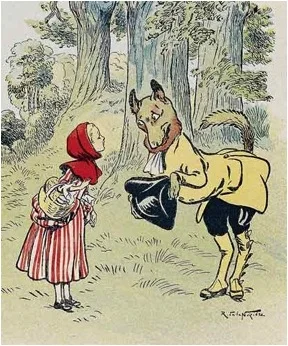

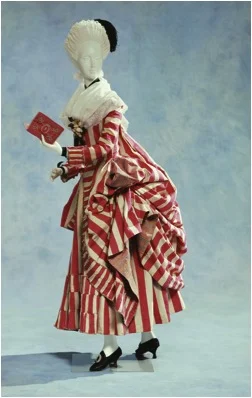

From the heroine’s namesake to the Wolf’s disguise, clothing is especially evident in the illustrations. The portrayed costumes remain antiquated despite the progression of time. In particular, there is a trend among illustrators to depict the characters in eighteenth-century dress. A comparison can be especially made between the portrayal of “Little Red Riding Hood” and surviving examples of eighteenth-century clothing from various museums. An interesting question arises: has the tale of “Little Red Riding Hood” become a vehicle for transmitting eighteenth-century fashion?

Like most fairytales, the writing of “Little Red Riding Hood” derives from peasant folklore. Originally part of an oral tradition, there were many versions of the story throughout Europe including the Italian tale of the “False Grandmother” and the French yarn known as “The Grandmother.”[i] Some folklore scholars even argue that the plot - a girl’s interaction with a wolf and its dire consequences for her grandmother - is medieval in origins.[ii]

Despite many variations of the oral tale, its written form has one definitive written origin. In 1697, the Frenchman Charles Perrault published a collection of tales titled, Histoires ou Contes du temps passé, avec es moralités (Stories or Tales of Past Times, with morals). Included among the story collection was the first publication of “Le Petite Chaperon Rouge.” Although later versions have relied on Perrault’s narrative, the tale’s seventeenth-century roots did not become a model for later illustrators. Instead, the nineteenth-century French artist Gustave Doré created a series of illustrations for “Little Red Riding Hood” that had a profound influence on later illustrators.[iii] In particular, Doré chose to represent his characters in eighteenth-century costume, or rather, in what he thought was a previous century’s style of dressing. Thus, the heritage of “Little Red Riding Hood” in literary form is a hybrid of a seventeenth-century text and nineteenth-century imagery.

Of all the articles of clothing mentioned and illustrated in “Little Red Riding Hood,” the red cape is the most memorable as well as the most faithfully maintained aspect of the story. After all, what would our heroine[iv] be called without her red cape? Yet, early tellings do not describe her hood as being red. It is likely that Perrault started the tradition of the iconic red cape.[v] In one version of the story written in the nineteenth century, the narrative beings with an explanation of how the little girl came to be named after her hood:

“This good woman had a little red riding hood made for her - the kind ladies wear to go riding - and it made her look so very pretty that everybody called her Little Red Riding-Hood.”[vi]

It is interesting that the term “riding hood” references equestrian wear for women, a fashion category that was greatly influenced by male tailoring. Perhaps the common red color of these cape garments derives from men’s military uniform. There are several surviving examples of red capes from the eighteenth century including the Red Wool Hooded Cape at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This cape or cardinal is made out of English wool broadcloth. Broadcloth was a popular textile for capes because of its felt-like texture, making it an ideal material for staying warm and dry. Another reason capes made out of broadcloth became a common garment for women was due to the boom in the wool trade.[vii] In The Fairy Book of 1913, the protagonist wears a red cape quite similar to the example at the Metropolitan Museum of Art with the hood attached to the cape.

Other garments worn by Little Red Riding Hood in fairytale illustrations are inspired by everyday dress from the eighteenth century such as the shift, the petticoat, and the apron. Early texts of the tale describe Little Red Riding undressing before getting into bed with the Wolf in disguise as her grandmother. For example, an 1885 text in French describes the scene:

“And each time she asked where she should put all her clothes; the bodice, the dress, the petticoat, the long stockings, the wolf responded: “Throw them into the fire, my child, you won’t be needing them any more.”[viii]

While there’s the mention of underpinnings fir Little Red Riding Hood’s outfit, illustrators often choose not to depict the moment possibly because it was not considered appropriate for a children’s book. Instead, artists more frequently represent the moment with the girl already in bed with the Wolf. One the most well-known images is by Doré, who depicts the heroine in what is most likely a linen shift. Several items from Colonial Williamsburg including their examples of a linen shift, corset and wool petticoat have textile parallels to this scene.

In Walter Crane’s 1875 series of illustrations for Red Riding Hood, there is an image illustrated in the beginning of the story when Little Red Riding Hood’s mother tells her to bring a basket of food to her grandmother. The young girl is shown wearing a white apron along with her signature red cape. And while aprons are apart of eighteenth-century attire for women and girls, they were not for everyday wear.[ix] For example, the English Embroidered Apron from Colonial Williamsburg, with its thin muslin material and ornately embroidered Dresden work, demonstrate how aprons were for intended for formal occasions and not a jaunt through the forest.

Despite this common misconception about aprons when depicting Little Red Riding Hood’s outfit, it nevertheless provides the opportunity to discuss the function of such an accessory in eighteenth-century fashion. Another point would be the similarity between the clothing of children and adults during the eighteenth century. Although the character of Little Red Riding Hood is a child, her clothing would be identical to that of an adult woman.[x] Consequently, both the description and representations of “Little Red Riding Hood” in children’s fairytale literature provide an opportunity to discuss aspects of dress during the eighteenth century ranging from the simple linen shift to the richly colored red cape.

Little Red Riding has also been shown in a dress reminiscent of a polonaise gown with the gathering of fabric in the back. This specific draping is made more obvious when looking at the Polonaise Striped Dress from the Kyoto Costume Institute. Yet like the apron, a Polonaise styled dress was an unlikely part of a woman’s everyday attire. Walter Crane’s and other illustrators’ interpretation of eighteenth-century clothing was more likely informed by what was worn by middle-class women during the nineteenth century, which included the changed function of the apron and the draping of fabric for a woman’s dress.

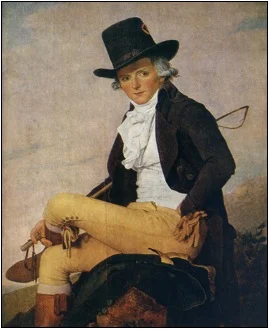

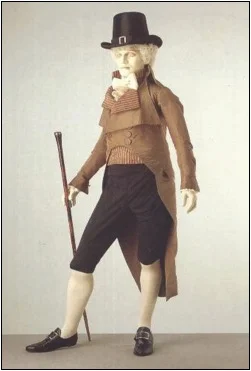

Little Red Riding Hood is not the only character to be antiquated costume. The attire of the Wolf gradually evolves to clothing that is also evocative of the eighteenth-century. Not only is there the difficulty of depicting a animal wolf in human clothing, but portraying his attire with an eighteenth-century flare adds to the challenge. In an early twentieth-century illustration, the Wolf is depicted wearing a coat, breeches, and a tricorner hat. This outfit is suggestive of a country gentleman’s suit, which can also seen in the painting Monsieur Seriziat by Jacques-Louis David. Although both the Wolf and Monsieur Seriziat wear a white ruffle and top boots, the fullness of the Wolf’s coat refers to a cut earlier than the late-eighteenth century coat as that worn by Monsieur Seriziat.

Illustrators rarely depicted the Wolf accurately when disguised as the grandmother. However, part of this inaccuracy is due to the lack of knowledge of what was actually worn for sleep during the eighteenth-century. It was possible that the linen shift, like the one from the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, functioned as a form of nightgown. For the book Household Stories from the Collection of Brothers Grimm in 1875, the Wolf is shown in guise of the Grandmother likely wearing a linen shift.

In the last quarter of the eighteenth century, fairytales for children’s literature fell out of favor and were criticized for their lack of moral pedagogy. Yet during the nineteenth century, these tales experienced a revival of popularity partly due to the Grimm Brothers.[xi] In 1812, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm published traditional German folklore and fairytales in the book Kinder und Hausmärchen (Children's and Household Tales) which included a retelling of “Little Red Riding Hood.”

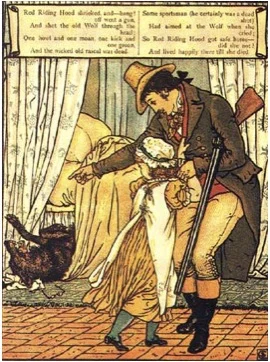

In contrast to Perrault, the Grimm’s take on “Little Red Riding Hood” has the addition of the Hunter as the heroic character who saves Little Red Riding Hood and her Grandmother.[xii] It makes sense that when the Hunter is depicted, he is often shown not in eighteenth-century garb, but clothing that is more reminiscent of the nineteenth century. Like the Wolf, the character of the Hunter does not always remain faithful to social norms. That being said, Walter Crane also did an illustration of the Hunter is a hybrid of late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century styles of clothing for a fashionable Englishman. In particular, the cut of the coat and the style of hat worn by the Hunter are evocative of an Englishman’s ensemble from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Through these musings of the similarities between eighteenth-century clothing and the illustrations of costume in “Little Red Riding Hood,” it is clear that the imaginary landscape found in the world of children’s literature contains traces of past centuries. Although illustrators have not always been historically faithful in their portrayal of eighteenth-century attire, these images nevertheless indicate a continuing fascination with clothing from the past as character signifiers. While “Little Red Riding Hood” is a tale about a girl named after her red cape, it is also a story where text, image, and fashion intersect to celebrate fashion history.

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Ahlstrom Appraisals | Personal Property Appraisals and Art Consultations | Serving Atlanta & Southeast

Fine Art, Antiques & Historic Materials

[i] Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales (Boston: Mariner Books, 1992), 412.

[ii] Jan Ziolkowski, “A Fairy Tale from before Fairy Tales: Egbert of Liege’s ‘De puella a lupellis seruata; and the Medieval Background of Little Red Riding Hood,” Speculum 67 (1992): 556.

[iii] Sandra Beckett, Sandra. “Recycling Red Riding Hood in the Americas” in Studies on Themes and Motifs in Literature: Interdisciplinary and Cross Cultural In North America. (New York: Peter Lang, 2005), 10.

[iv] Different versions of the tale call the heroine by several names all of which reference a red colored garment for outerwear (e.g. Red Cape, Red Cap, Little Red Riding Hood).

[v] Mary Douglas, “Red Riding Hood: An Interpretation from Anthology,” Folklore 106 (1995): 4.

[vi] The Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault, (London: The Folio Society, 1998), 27.

[vii] Elizabeth Ewing, Everyday Dress: 1650-1900 (New York: Chelsea House Publications, 1984), 35.

[viii] Jones, Steven Swann. “On Analyzing Fairy Tales: “Little Red Riding Hood” Revisited,” Western Folklore 46 (1987): 104.

[ix] Class notes.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ségolène Le Men, “Mother Goose Illustrated: From Perrault to Doré,” Poetics Today 13 (1992): 23.

[xii] In the Perrault version of “Little Red Riding Hood,” it is the heroine’s own cunning that saves her from the Wolf. See Jones, Steven Swann. “On Analyzing Fairy Tales: “Little Red Riding Hood” Revisited,” Western Folklore 46 (1987).