Warhol’s Replication of American IconS

What do a chair, a cow, and a movie star have in common when portrayed in Pop Art? In the case of Andy Warhol’s silk-screens, this seemingly incongruous group is unified by the principle of repetition. Warhol employed the compositional device of the repeated image as a means to critique mass culture in an ironic manner. While duplication in Little Electric Chair explores the media’s objective communication of death, Cow Wallpaper elevates the banal through its decorative pattern. In the instance of Marilyn Monroe, the reproduced and transformed portrait expresses the nature of public devotion of the tragic celebrity. Thus, Warhol subverts the symbology of the American icon in a repetitive manner.

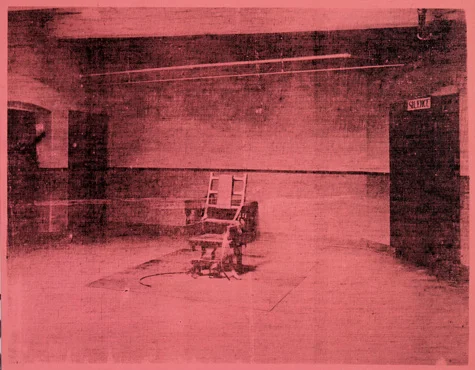

In Warhol’s double image of Little Electric Chair (1964–1965), replication is employed as a means to provide a layered critique of the media’s portrayal of death. As the title indicates, the focus of the work is the electric chair which ironically takes up minimal space in the composition despite its central role.

Through the stark setting of an empty room, the viewer is encouraged to concentrate on the iconographic meaning of the seemingly diminutive chair with its potent ability to kill. Warhol’s appropriation of the image from a photographic medium provides a sense of the way mass media covers death in an objective documentary format.

This initial objectivity of the Little Electric Chair is further conveyed by a lack of incident in which the actual act of execution is excluded. The omnipresence of death is evoked in the image’s eerie stillness.

In order to infuse emotion into the media’s detached black-and-white representation, Warhol inflects color into the monochromatic scheme. The electric chair, silk-screened in black and a muted silver, conforms to the traditional Western color associations with death and dismal darkness. Warhol accentuates this black obscuration to make his version of the image difficult to decode in contrast to the normally identifiable images of mass culture.

While the concealing nature of black challenges the viewer to decipher meaning, the use of pink strikingly illuminates the theme of death through unconventional means. The left-to-right transition of the viewer’s observation is jolted not only by the separation of canvas between the works but also by the surprising use of bright pink.

Often viewed as a light-hearted hue, the application of vibrant pink in a deathly setting creates a disconcerting juxtaposition between the austere subject matter and the flamboyant style. Unlike the silver version, the lighter tone of the pink allows the sign of SILENCE hovering above the distant door to be seen. The quietude of the scene is ironically reinforced by the dynamic color of purple.

As can be seen, the contrasting color schemes of silver and pink reveal how the same depiction can dramatically change in mood and thus affect the interpretation. By subverting the media’s conventional use of color and scale, Warhol challenge’s the cultural tendency to disengage and distance oneself during the act of looking, even in regards to death.

As exemplified by the two images of electric chairs, insistent repetition forces the viewer to take a stand with political issues such as the death penalty. Thus, Warhol duplicates the icon of the electric chair in order to complicate its meaning and reinvigorate public reaction towards death.

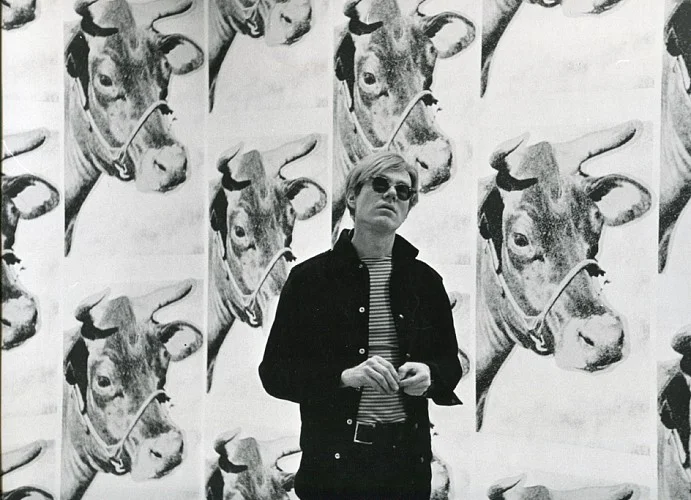

While duplication in Little Electric Chair compels the viewer to be aware of the act of looking, the repeated pattern of Cow Wallpaper (1971) draws attention to the process of artistic production. Directly applied to the wall without traditional framing, Cow Wallpaper blurs the boundaries between the decorative and fine art.

Although the wallpaper functions as a decorative backdrop, as evidenced by the photographs hanging on top, the larger-than-life image of unnaturally colored cows overwhelms the surface space. This assertion of presence is accentuated by the jarring brightness of the blue background and the staggering of a multitude of yellow heads.

Similar to the use of purple in Little Electric Chair, the high-key coloration of the cows creates a dynamic optical effect which is then magnified by the pattern’s scale. As the composition wraps around the corner, the flatness of the image transgresses into three-dimension further encroaching on the viewer’s physical space.

Such monumentality of a banal subject matter acts as a comic assault upon the viewer who unexpectedly is forced to engage with the décor before examining the hanging artwork.

Unlike the controversial significance of an Electric Chair in relation to execution, the iconography of a cow would be considered to have neutral meaning in popular culture as a symbol of rural plenty. However, Warhol subversively visually elevates the banal jersey cow through an unorthodox use of color and scale yet also renders its significance as meaningless through the unorthodox use of color and its repeated representation.

Upon closer examination, slippages in the silk-screen process are revealed in which marks of black paint appear in an almost accidental manner; however, the haphazardness of the paint is ironically intentional as it provides differentiation in the seemingly uniform composition.

Despite the repetition of the same bovine animal, each one is made unique by the artist’s ‘flawed’ application. By allowing this irregularity in the artistic production, Warhol provides difference in the seemingly redundant pattern.

Through the tensions of repeated banality and artistic originality, Warhol’s wallpaper of repeated cow imagery is transformed into a confrontational artwork that is both humorous and ambiguous.

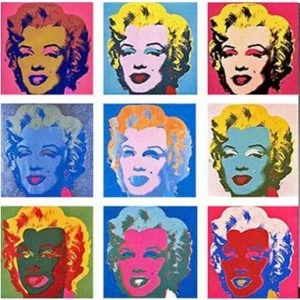

In contrast to the duplication of a deadly chair or the replication of a common cow, the singularity of Marilyn Monroe (1967) echoes contemporary American culture’s fascination with celebrity. While banality is satirically elevated through the repetition of a type of animal in Cow Wallpaper, the glorification of glamour in Marilyn Monroe is singularly elevated at the expense of a specific individual.

In accordance with the sexual persona of the Hollywood actress, Warhol emphasizes her sexuality. The ‘pop’ effect of bright color accentuates the lips and eyelids, areas to which makeup is traditionally applied. The vivid and feminine pink contrasts with the murky yellow skin and brown hair.

Similar to the jarring coloration in the previous silkscreen works (a pink electric chair or a yellow cow), the unnatural palette of the normally fair-skinned, blonde actress contradicts the viewer’s expectations. Once again, Warhol appropriates the image of the actress from press coverage as evidence by the black outline of the single headshot. The frontality and focus of the face are reminiscent of traditional saint iconography in which Marilyn’s likeness is transformed into a symbolic canonization of the desirable female.

While colorful artificiality of verisimilitude subtly comments on popular culture’s objectification of Marilyn, the sense of enclosure of the solitary figure is evoked through presentation. Rather than direct contact with the work’s surface as in Cow Wallpaper or Little Electric Chair, the work and viewer are physically separated through the traditional framing of a matt and glass.

Thus, the method of display alludes to the personal isolation that can be experienced as a result of fame. In fact, Marilyn’s suicide is often associated with her experience of extreme individuation as Warhol has visually expressed.

While the pairing in Little Electric Chair comments on the objectivity of death in society, the singleness of Marilyn Monroe suggests a personal tragedy of self. By reproducing the famous Hollywood icon in Marilyn Monroe, the manipulation of identity through image-making both endorses and critiques mass culture’s celebration of individualism.

As can be seen, Warhol’s use of visual redundancy distorts the conventional significance of an iconic image. The media’s dispassionate depiction of the death penalty is given greater emotional meaning in Little Electric Chair through its two monochromatic scenes.

Another reworking of a standard symbol occurs in Cow Wallpaper as the repetitive decoration simultaneously elevates the abstracted form of the cow while nullifying its meaning. Tensions between uniformity and uniqueness occur not only in the flawed silk-screening of the cow pattern but also in the mass production of the individual in Marilyn Monroe. The lone image of Marilyn, with its lacking formal repetitiveness, highlights the issue of public appropriation of personal identity.

So what do the iconography of death, banality, and celebrity have in common? For Warhol, it’s the repeated American objectification of their meaning.

Enjoyed reading? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sources:

Boudon, D. Warhol. Harry N. Abrams Inc., London, 1989.

Dyer, J. “The Metaphysics of the Mundane: Understanding Andy Warhol’s Serial Imagery,” Artibus et Historiae, 25, 2004, pp.33-47.

Harrison, C. and Wood, P. Ed. Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas,, Oxford, 2003.

Hopkins, D. After Modern Art: 1945-2000, Oxford, 2000.

© Courtney Ahlstrom Christy 2014